Your browser window currently does not have enough height, or is zoomed in too far to view our website content correctly. Once the window reaches the minimum required height or zoom percentage, the content will display automatically.

Alternatively, you can learn more via the links below.

Humans have five traditional senses: sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. We go about the world using these senses to guide us, and we are heavily reliant on vision as our primary and dominant sense.

Many animals share these same senses as we do, and different species prioritise different senses. For example, dogs rely on smell as their dominant sense.

Some species also have senses entirely different from ours, each helping them understand the world in its own way.

An Immense World by Ed Yong explores the senses of different animals and how they might reveal the hidden worlds around us.

He asks if humans know the world through sight, what could a world look like otherwise?

Here are some interesting things he uncovered about animal senses and what each means for the species’ lives they shape.

Are humans the best at seeing? It would appear not. Though our vision is excellent, many animals outperform us.

Eagles and other birds of prey have substantially sharper vision than ours. The wedge-tailed eagle views the world in more than twice our resolution and can spot prey from over a mile away.

Some spiders, with their eight eyes as opposed to two, see 360 degrees around them, something humans can’t do.

Chameleons don’t ever have to turn their heads to look around, because their two eyes can move independently of each other; they can look in front and behind at the same time.

The killer fly has ultrafast vision that allows it to capture quick-flying insects in the span of a human blink. Even scallops have surprisingly sophisticated sight: the tiny blue dots lining their shells are eyes, each with its own pupil.

Have you ever heard someone say that dogs are colourblind? Well, they’re wrong. Dogs do see colours, just not as many as we do.

Light spans a range of wavelengths, and humans only see a subset of them. Other species can detect wavelengths we can’t. Many birds, reptiles, insects and fish, for example, can see ultraviolet light.

Animal senses are tuned to the temperatures in which they live. A camel isn’t as distressed by the desert sun as we are, and penguins aren’t that bothered by the chill Antarctic air.

Cold-blooded animals, with their ability to regulate their body temperature so drastically, take this a step further. Some can also sense heat radiating elsewhere.

Some snake species, for example, have heat-sensitive pits that detect infrared radiation. This helps them sense heat from the bodies of mice and other prey.

Sea otters have ultra-sensitive paws, more sensitive than human hands, that enable them to identify food on the sea floor quickly.

Star-nosed moles use their unique, star-shaped snout to feel their way through soil, building a tactile map of their surroundings. They can identify prey, swallow it, and begin searching for the next mouthful in the time it takes a human to blink.

Seals read the water through their whiskers, which can track the wake of a fish from nearly 200 yards away.

Alligators rely on pressure-sensing domes along their jaws to detect tiny vibrations at the water’s surface – even a single falling droplet.

Just as humans can feel earthquake tremors, some animals can detect faint surface vibrations with specialised receptors.

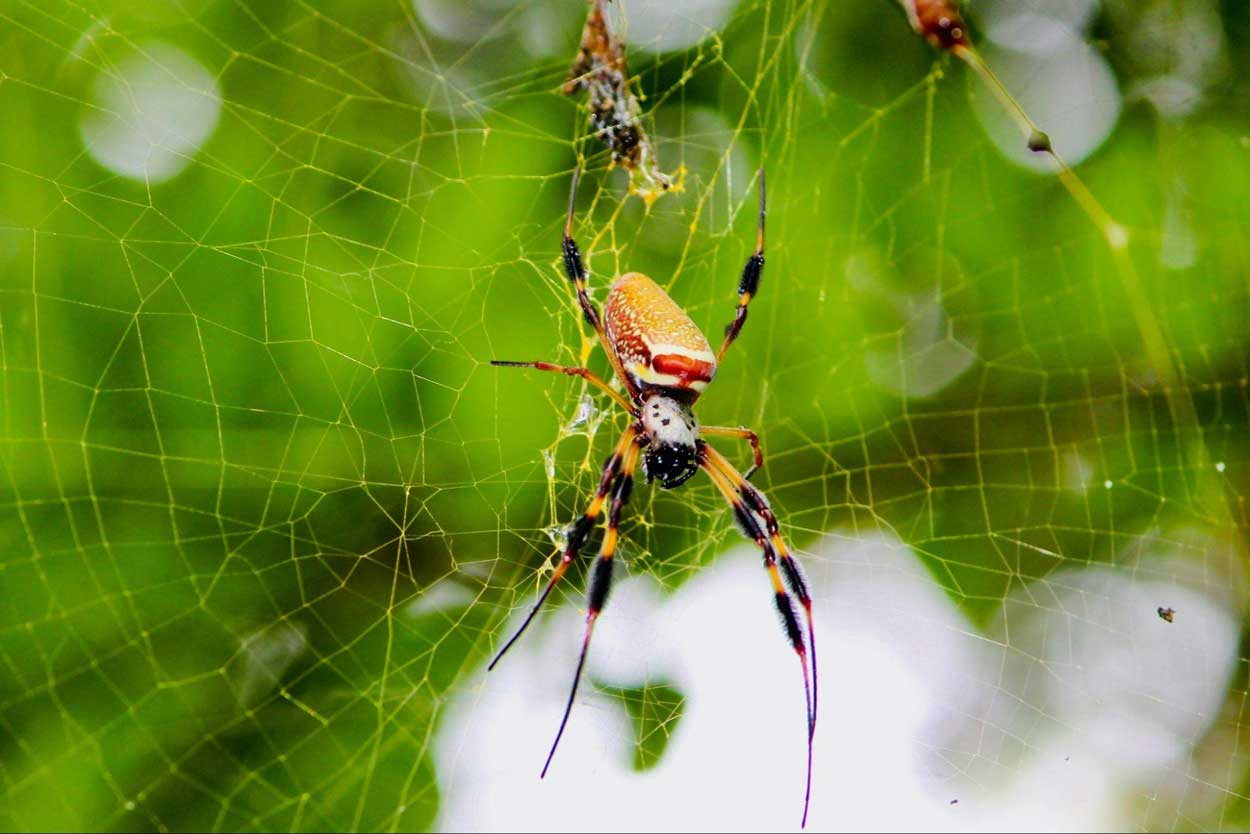

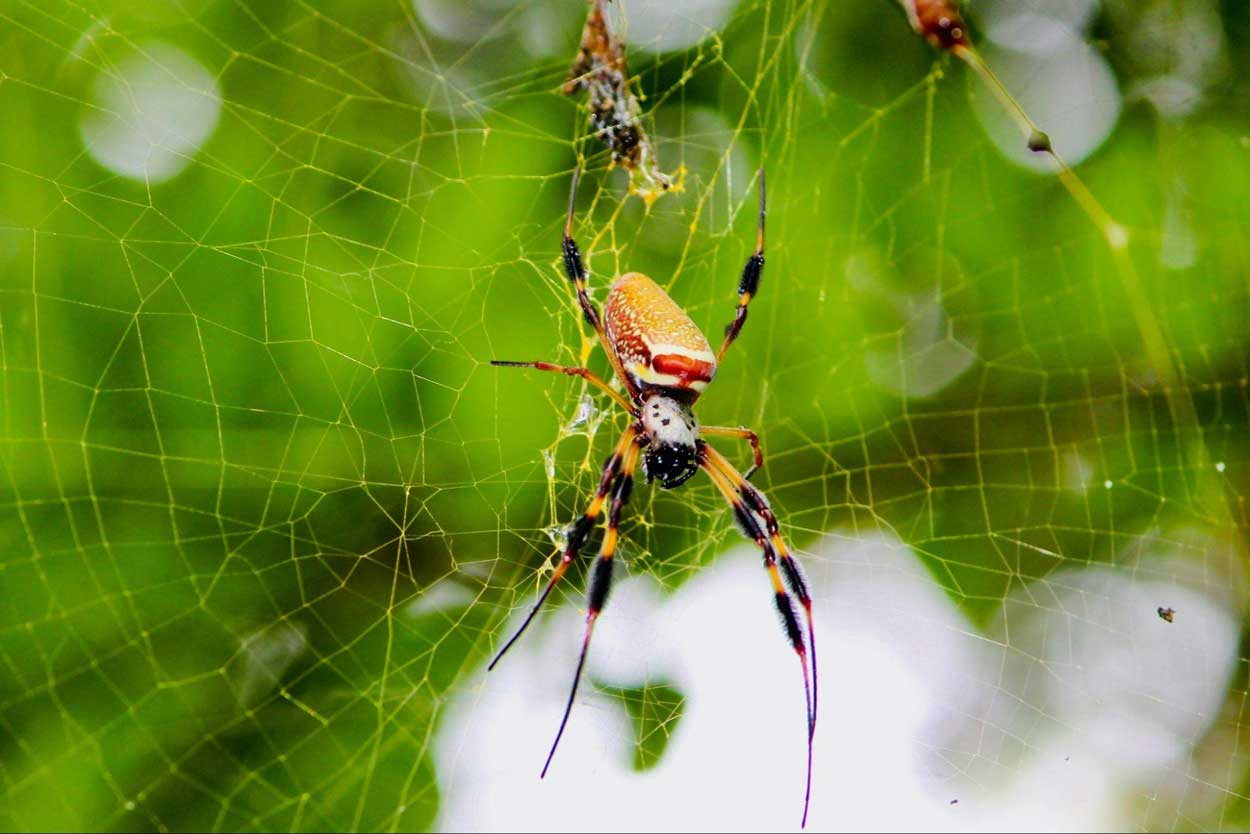

Sand scorpions use vibration-sensitive feet to locate prey by its footsteps. Spiders do something similar: they sense anything that touches their web through vibrations. In fact, scientists have found that an orb-weaver’s web functions as part of its sensory system, making the spider and web a single unit.

Owls are expert listeners, able to pinpoint prey through the faintest sounds.

Birds hear frequencies similar to those of humans, but on a much faster timescale. A song that sounds like three notes to us may contain five or six to them. Zebra finches, for instance, sing so quickly that we miss subtle variations that help them recognise one another.

Some whales, meanwhile, use infrasound to communicate across entire oceans, navigating and connecting through vast acoustic maps.

Very few animals have the skills to detect their surroundings through echolocation, and only toothed whales (dolphins, orcas, sperm whales) and bats have really perfected this sense.

Bats unleash a stream of short, ultrasonic pulses from their mouth. They then listen for returning echoes and detect and locate objects around them. It’s almost like a game of Marco Polo, a bat will speak, and the world shouts back. As nocturnal animals, they can use this sense to detect prey incredibly fast.

Dolphins do the same underwater. The U.S. Navy even trained dolphins to rescue lost divers and equipment because of their superior ability to find things underwater. Dolphins can distinguish between cylinders filled with water and those filled with alcohol, and between steel and brass objects, using echoes.

Electric eels deliver pulses that force the muscles of prey to pulse and vibrate, revealing their location. Stronger pulses can paralyse the prey.

Sharks and rays don’t produce their own electric fields, but can detect the electric fields of other animals, which help them catch prey.

The study of electric fish inspired the design of the first synthetic battery.

The Earth has a magnetic field, and some animals have tuned in to it to help them find their way. While humans use compasses that detect this field, some animals have compasses built into their sensory systems. This is called magnetoreception.

Loggerhead turtles can go all around the ocean and find their way back to the same beach where they hatched, and they do so by recognising magnetic signposts.

Other species, such as robins, have also developed magnetoreception. It is common in species that have to travel long distances.

Humans have five traditional senses: sight, sound, smell, touch and taste. We go about the world using these senses to guide us, and we are heavily reliant on vision as our primary and dominant sense.

Many animals share these same senses as we do, and different species prioritise different senses. For example, dogs rely on smell as their dominant sense.

Some species also have senses entirely different from ours, each helping them understand the world in its own way.

An Immense World by Ed Yong explores the senses of different animals and how they might reveal the hidden worlds around us.

He asks if humans know the world through sight, what could a world look like otherwise?

Here are some interesting things he uncovered about animal senses and what each means for the species’ lives they shape.

Are humans the best at seeing? It would appear not. Though our vision is excellent, many animals outperform us.

Eagles and other birds of prey have substantially sharper vision than ours. The wedge-tailed eagle views the world in more than twice our resolution and can spot prey from over a mile away.

Some spiders, with their eight eyes as opposed to two, see 360 degrees around them, something humans can’t do.

Chameleons don’t ever have to turn their heads to look around, because their two eyes can move independently of each other; they can look in front and behind at the same time.

The killer fly has ultrafast vision that allows it to capture quick-flying insects in the span of a human blink. Even scallops have surprisingly sophisticated sight: the tiny blue dots lining their shells are eyes, each with its own pupil.

Have you ever heard someone say that dogs are colourblind? Well, they’re wrong. Dogs do see colours, just not as many as we do.

Light spans a range of wavelengths, and humans only see a subset of them. Other species can detect wavelengths we can’t. Many birds, reptiles, insects and fish, for example, can see ultraviolet light.

Animal senses are tuned to the temperatures in which they live. A camel isn’t as distressed by the desert sun as we are, and penguins aren’t that bothered by the chill Antarctic air.

Cold-blooded animals, with their ability to regulate their body temperature so drastically, take this a step further. Some can also sense heat radiating elsewhere.

Some snake species, for example, have heat-sensitive pits that detect infrared radiation. This helps them sense heat from the bodies of mice and other prey.

Sea otters have ultra-sensitive paws, more sensitive than human hands, that enable them to identify food on the sea floor quickly.

Star-nosed moles use their unique, star-shaped snout to feel their way through soil, building a tactile map of their surroundings. They can identify prey, swallow it, and begin searching for the next mouthful in the time it takes a human to blink.

Seals read the water through their whiskers, which can track the wake of a fish from nearly 200 yards away.

Alligators rely on pressure-sensing domes along their jaws to detect tiny vibrations at the water’s surface – even a single falling droplet.

Just as humans can feel earthquake tremors, some animals can detect faint surface vibrations with specialised receptors.

Sand scorpions use vibration-sensitive feet to locate prey by its footsteps. Spiders do something similar: they sense anything that touches their web through vibrations. In fact, scientists have found that an orb-weaver’s web functions as part of its sensory system, making the spider and web a single unit.

Owls are expert listeners, able to pinpoint prey through the faintest sounds.

Birds hear frequencies similar to those of humans, but on a much faster timescale. A song that sounds like three notes to us may contain five or six to them. Zebra finches, for instance, sing so quickly that we miss subtle variations that help them recognise one another.

Some whales, meanwhile, use infrasound to communicate across entire oceans, navigating and connecting through vast acoustic maps.

Very few animals have the skills to detect their surroundings through echolocation, and only toothed whales (dolphins, orcas, sperm whales) and bats have really perfected this sense.

Bats unleash a stream of short, ultrasonic pulses from their mouth. They then listen for returning echoes and detect and locate objects around them. It’s almost like a game of Marco Polo, a bat will speak, and the world shouts back. As nocturnal animals, they can use this sense to detect prey incredibly fast.

Dolphins do the same underwater. The U.S. Navy even trained dolphins to rescue lost divers and equipment because of their superior ability to find things underwater. Dolphins can distinguish between cylinders filled with water and those filled with alcohol, and between steel and brass objects, using echoes.

Electric eels deliver pulses that force the muscles of prey to pulse and vibrate, revealing their location. Stronger pulses can paralyse the prey.

Sharks and rays don’t produce their own electric fields, but can detect the electric fields of other animals, which help them catch prey.

The study of electric fish inspired the design of the first synthetic battery.

The Earth has a magnetic field, and some animals have tuned in to it to help them find their way. While humans use compasses that detect this field, some animals have compasses built into their sensory systems. This is called magnetoreception.

Loggerhead turtles can go all around the ocean and find their way back to the same beach where they hatched, and they do so by recognising magnetic signposts.

Other species, such as robins, have also developed magnetoreception. It is common in species that have to travel long distances.

Have you ever heard of a national dish? No doubt you’re aware of a national anthem or a national flag, but what is a national dish?

While you may have heard of Christmas and Hanukkah, did you know that there’s also an important Buddhist celebration and a Wiccan festival in the same month?

There is a common myth around the world that there is one universal sign language that Deaf people use to communicate. But this is far from the truth – there are many sign languages!

Greek mythology is a collection of stories about gods, heroes, monsters, and the beliefs of Ancient Greece.

Help keep the momentum going. All donations will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. If you would like to pay directly into our bank account to avoid the processing fee, please contact donate@abouttime.org.au. ABN 67 667 331 106.

Help us get About Time off the ground. All donations are tax deductible and will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

Leave a Comment

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.