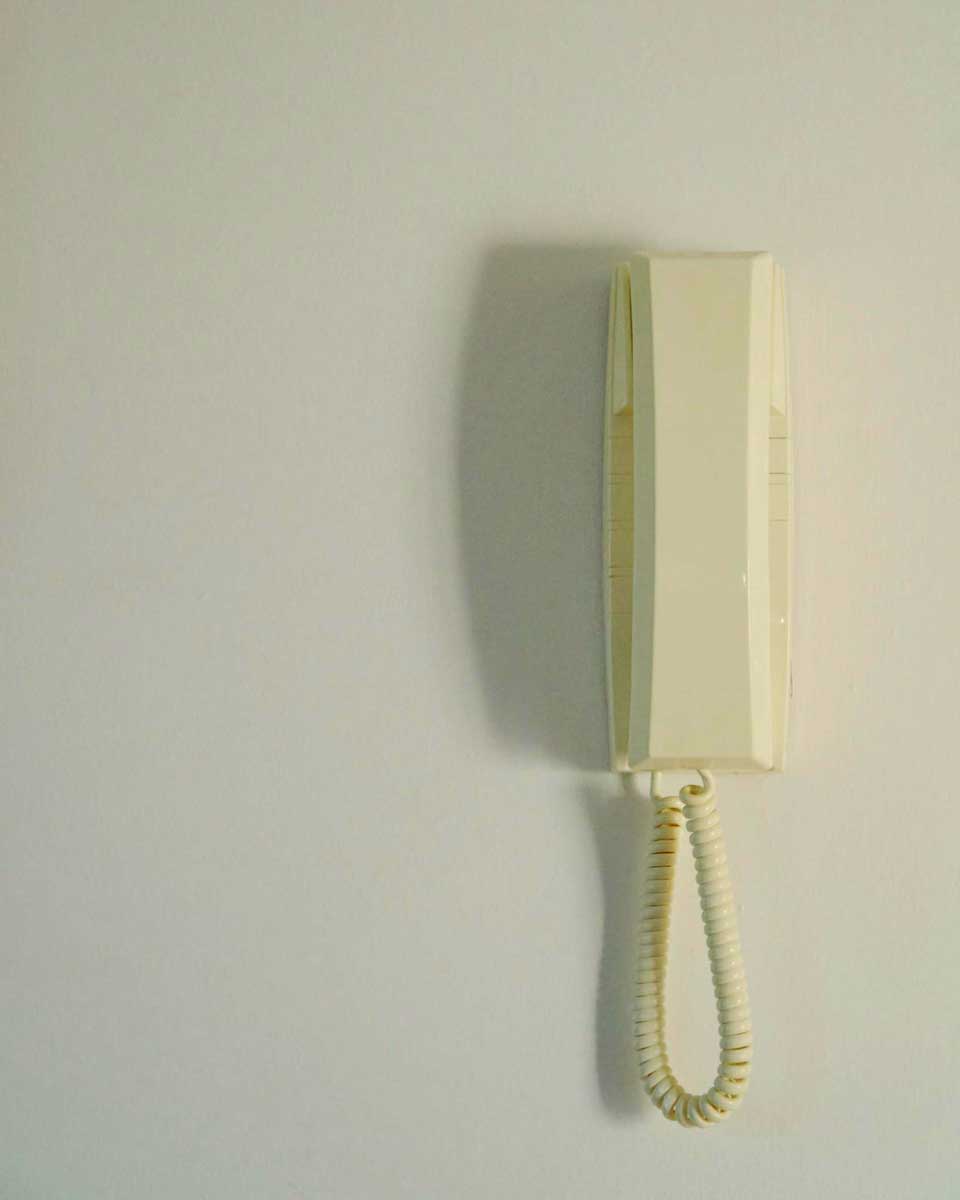

In prison, silence isn’t always golden. It’s just another form of the unknown, another form of loss of control, another avenue for the negative thoughts to take.

When the phone call isn’t answered, the letter not replied to or the email not received – was it lost? Was it missed? Was it ignored? Was it never received, or did they simply not know how to reply?

Communication while in prison is always haunted by the unknowns, the maybes, with all the possibilities hanging over every word. All of these shape how we communicate with the outside world and shape our perception of it, which shapes our perception of how time passes for those we love. It distorts it and warps it.

It makes the 10 minutes during the call pass like seconds and the 10 minutes between calls feel like hours. The days between emails feel like months of silence. The weeks between letters feel like months of abandonment. It stretches the waiting and increases the hurt.

Communication is hard for most people, and the limitations placed on inmates and their loved ones amplify this to higher levels of frustration. Pair this with the changes forced on new inmates and their family, and it can lead to abandonment of ties between inmates and their friends and family or the projection of frustration onto those on the outside, leading to a loss of connections.

For some, these problems are further increased by limited reading and writing ability, limited funds for phone calls or being unable to adapt to all the changes in time before damage to already fragile relationships has been done. For many inside, once that damage has been done, there is no way to work on repairing it. And, contrary to the old saying, time does not heal all. It increases the gap between the two parties – sometimes to impossible distances.

This loss of connection can occur at a critical point in an inmate’s life. Connection to the outside world is important for mental wellbeing, where projected frustration can negatively influence people on the outside who are already unsure about maintaining a relationship. This can lead to increasing disconnection between the inmates and the outside world, potentially leading to a complete loss of communication and increased isolation during and after incarceration.

I put out the call to all inmates to remember that there are many reasons a call might go unanswered or a letter un-replied to and not to assume the worst. I also ask those on the outside to remember that there are many reasons for frustration in prison. If any of it leaks out in communication, it is not intentional – just a side effect of the difficulties of communication.

In prison, silence isn’t always golden. It’s just another form of the unknown, another form of loss of control, another avenue for the negative thoughts to take.

When the phone call isn’t answered, the letter not replied to or the email not received – was it lost? Was it missed? Was it ignored? Was it never received, or did they simply not know how to reply?

Communication while in prison is always haunted by the unknowns, the maybes, with all the possibilities hanging over every word. All of these shape how we communicate with the outside world and shape our perception of it, which shapes our perception of how time passes for those we love. It distorts it and warps it.

It makes the 10 minutes during the call pass like seconds and the 10 minutes between calls feel like hours. The days between emails feel like months of silence. The weeks between letters feel like months of abandonment. It stretches the waiting and increases the hurt.

Communication is hard for most people, and the limitations placed on inmates and their loved ones amplify this to higher levels of frustration. Pair this with the changes forced on new inmates and their family, and it can lead to abandonment of ties between inmates and their friends and family or the projection of frustration onto those on the outside, leading to a loss of connections.

For some, these problems are further increased by limited reading and writing ability, limited funds for phone calls or being unable to adapt to all the changes in time before damage to already fragile relationships has been done. For many inside, once that damage has been done, there is no way to work on repairing it. And, contrary to the old saying, time does not heal all. It increases the gap between the two parties – sometimes to impossible distances.

This loss of connection can occur at a critical point in an inmate’s life. Connection to the outside world is important for mental wellbeing, where projected frustration can negatively influence people on the outside who are already unsure about maintaining a relationship. This can lead to increasing disconnection between the inmates and the outside world, potentially leading to a complete loss of communication and increased isolation during and after incarceration.

I put out the call to all inmates to remember that there are many reasons a call might go unanswered or a letter un-replied to and not to assume the worst. I also ask those on the outside to remember that there are many reasons for frustration in prison. If any of it leaks out in communication, it is not intentional – just a side effect of the difficulties of communication.

Your contributions are the centerpiece of the paper. If you would like to contribute to our Letters section, please send your letters to the below postal address:

Or via email:

On 1 November 2025, QCS introduced a new pricing model: 20 cents per minute for all calls, mobile or local. A call that once cost 30 cents for 15 minutes now costs $3 – a ten-times increase.

I have been incarcerated for 22 months of a four-year sentence in Queensland jails. This poem is about my own situation.

Reading other prisoner’s stories inspired me to keep my head up and keep going now four months in, thank you all who share your stories and words of wisdom.

I moved units about a month ago and we feed some stray cats here. One even let me pat her last night! It's been over a year since I've patted an animal, so you can imagine how excited I was!

Help keep the momentum going. All donations will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. If you would like to pay directly into our bank account to avoid the processing fee, please contact donate@abouttime.org.au. ABN 67 667 331 106.

Help us get About Time off the ground. All donations are tax deductible and will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

Your browser window currently does not have enough height, or is zoomed in too far to view our website content correctly. Once the window reaches the minimum required height or zoom percentage, the content will display automatically.

Alternatively, you can learn more via the links below.

Leave a Comment

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.