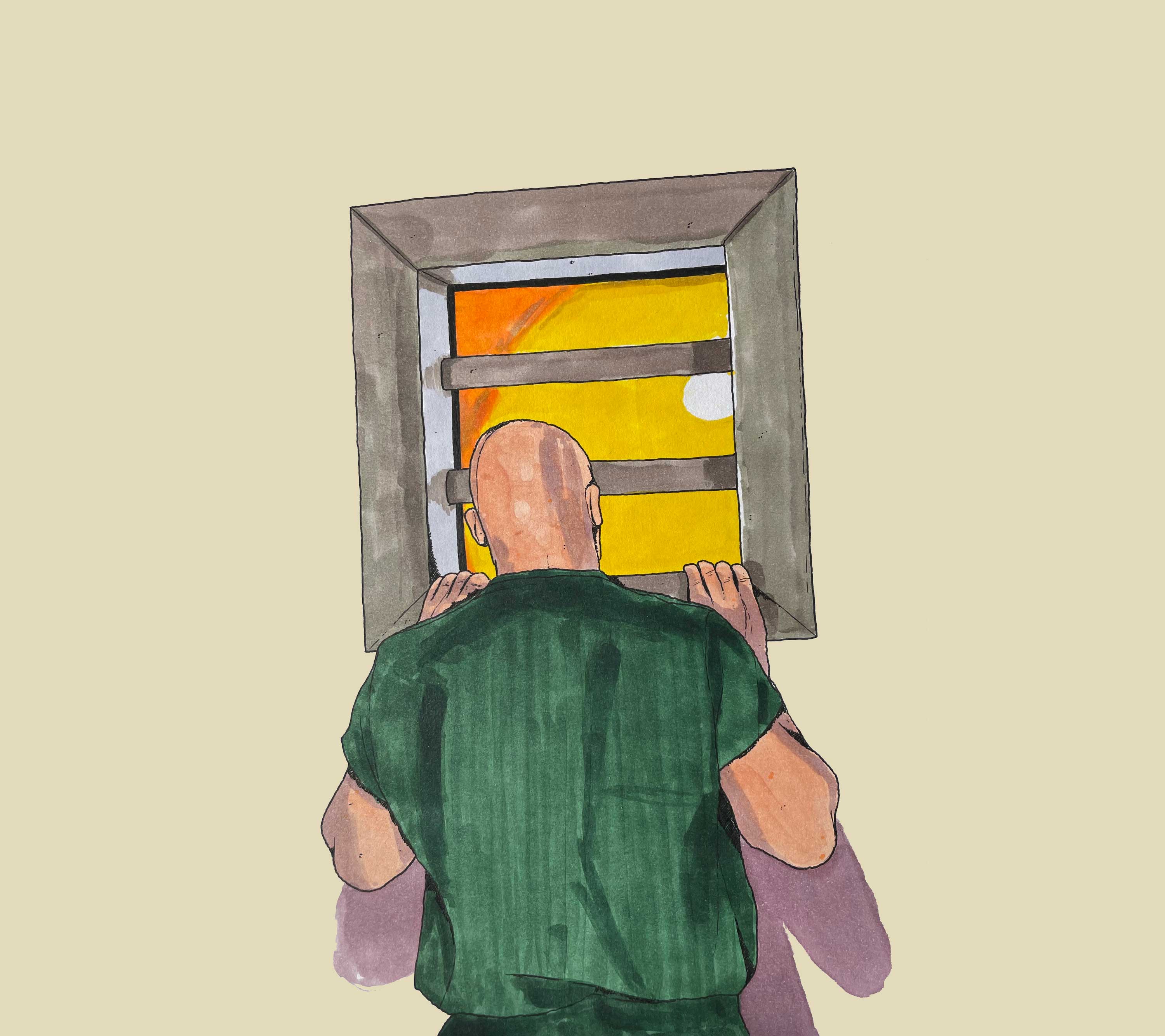

In mid-January, temperatures at the Loddon Prison Precinct in Victoria hit more than 42 degrees, while a significant bushfire raged just 10 kilometres away.

The only relief for the incarcerated came from small desk fans that must be purchased from buy-up, and cost $45 at the Loddon prison.

Sarah’s* partner is incarcerated at Loddon prison, and said that the heat leads everyone to get “cranky and irritable”.

“My partner has really been struggling with the heat, all they have is one small fan in their room,” Sarah told About Time.

“I just tell him to keep drinking water so he doesn’t get heat stroke. I understand they’re in prison but I do wish they had more cooling available.”

For several days following the fire, power was not fully restored at the prison, and those incarcerated there had no access to TV or radio.

The recent situation at Loddon is common in prisons around the state and country.

It comes as people in prisons around the country face extreme heat during the summer period.

The conditions at the Metropolitan Remand Centre in Melbourne were “stifling” this summer one man said.

A woman whose partner was on a separation order at the centre during the January heat wave said he was kept in lockdown all day with no air-conditioning and “constant heat blowing” into the cell.

“He was just using wet towels and sitting there naked and having cold showers constantly,” they told About Time.

At Hopkins Correctional Centre in Ararat, there is only air-conditioning in the prison officers’ watch posts, and the library, and the water temperature of the showers can’t be turned down so people can have a cold shower to cool down.

A number of prison watchdogs around the country have warned of “stifling” and “extreme” heat in ageing and poorly ventilated facilities, and have repeatedly called for better climate control through air-conditioning, fans and more shade in outdoor areas.

Despite the extreme temperatures recorded across Australia during summer, and that most prisons are located in regional areas that are typically hotter than cities, most prisons still do not have air-conditioning and other temperature controls.

In mid-January, temperatures at the Loddon Prison Precinct in Victoria hit more than 42 degrees, while a significant bushfire raged just 10 kilometres away.

The only relief for the incarcerated came from small desk fans that must be purchased from buy-up, and cost $45 at the Loddon prison.

Sarah’s* partner is incarcerated at Loddon prison, and said that the heat leads everyone to get “cranky and irritable”.

“My partner has really been struggling with the heat, all they have is one small fan in their room,” Sarah told About Time.

“I just tell him to keep drinking water so he doesn’t get heat stroke. I understand they’re in prison but I do wish they had more cooling available.”

For several days following the fire, power was not fully restored at the prison, and those incarcerated there had no access to TV or radio.

The recent situation at Loddon is common in prisons around the state and country.

It comes as people in prisons around the country face extreme heat during the summer period.

The conditions at the Metropolitan Remand Centre in Melbourne were “stifling” this summer one man said.

A woman whose partner was on a separation order at the centre during the January heat wave said he was kept in lockdown all day with no air-conditioning and “constant heat blowing” into the cell.

“He was just using wet towels and sitting there naked and having cold showers constantly,” they told About Time.

At Hopkins Correctional Centre in Ararat, there is only air-conditioning in the prison officers’ watch posts, and the library, and the water temperature of the showers can’t be turned down so people can have a cold shower to cool down.

A number of prison watchdogs around the country have warned of “stifling” and “extreme” heat in ageing and poorly ventilated facilities, and have repeatedly called for better climate control through air-conditioning, fans and more shade in outdoor areas.

Despite the extreme temperatures recorded across Australia during summer, and that most prisons are located in regional areas that are typically hotter than cities, most prisons still do not have air-conditioning and other temperature controls.

Prisons in some of the hottest parts of Australia, such as the Alice Springs Correctional Centre, do not have air-conditioning at all, despite decades of campaigning and recommendations from the Ombudsman, who has found that temperature in the cells can reach 34 degrees.

After a number of men attempted to escape this heat in the cells and tore a hole in the ceiling, the Northern Territory government did a comprehensive assessment to improve ventilation, with plans to put in more shading and evaporative cooling and airflow systems. But it does not plan to install air-conditioning.

Roebourne Regional Prison in Western Australia is commonly regarded as the hottest prison in the country. In July this year, following more than a decade of campaigning by advocates, the state government confirmed that all the cells at the prison now had air-conditioning.

The Tasmanian prison watchdog in 2018 raised serious concerns with extreme heat at the Launceston Reception Prison, saying that “female prisoners were seen coming out of cells gasping for air and dehydrated”.

“The female cells back onto a solid brick wall, which is a heat conductor, and there is no air ventilation,” the inspector said at the time.

The inspector found that concerned staff had recorded temperatures of up to 40 degrees at the prison over two nights in summer.

Following a recent inspection of the Bathurst Correctional Centre, the NSW prison inspector said that some areas of the prison were “dark, dilapidated, susceptible to extreme temperatures [and] lacking ventilation and natural light”.

It also said that the area set aside for people in prison to have video calls with their loved ones exposed them to extreme temperatures.

The inspector also said that heat at the Broken Hill Correctional Centre was “stifling”, with little relief available to those incarcerated there.

“The men had no capacity to cool down other than by using the water tap on top of the toilet cistern,” the inspector said.

The infrastructure at these prisons is from the 1800s, with windows that are always open, with temperatures at the prison ranging from -2.9 to 46.3 degrees, the watchdog found.

A spokesperson for NSW Corrections said that a Heat Event Response Plan is implemented during extreme heat, with enhanced ventilation, adjustments to daily routines during peak heat periods, additional hydration points and increased medical monitoring.

“To help manage heat inside accommodation areas, centres use a range of measures such as insulation, building design, air-conditioning where installed, and natural ventilation systems,” the spokesperson said.

“These approaches typically keep internal temperatures about eight to 12 degrees cooler than outside conditions.”

In Queensland prisons, air flow and temperature levels are monitored regularly, and there is a specialised unit within Queensland Corrective Services which “closely monitors and provides advice about how to manage high-risk weather, including heatwaves”.

Under a “safer cell design” program, more than 90 percent of prison cells in Queensland now have air-conditioning by default.

In Victoria, air-conditioning is only available in some accommodation units for “more vulnerable people”, a spokesperson said, including pregnant women, those with babies and the elderly.

In the ACT’s Alexander Manonochie Centre, the only cells with air-conditioning are in the Crisis Support Unit, with no plans to install cooling more widely.

The cells at the prison are designed “using passive solar principles, incorporating features such as strategic window placement, wall orientation, insulation and flooring materials to reduce heat during warmer months”.

There are no nation-wide policies or guidelines for managing extreme heat in Australian prisons, or for the regular measurement of temperatures within prison buildings and cells.

The “Guiding principles for corrections in Australia” from 2018 does not mention heat or temperature guidelines.

Prisons in some of the hottest parts of Australia, such as the Alice Springs Correctional Centre, do not have air-conditioning at all, despite decades of campaigning and recommendations from the Ombudsman, who has found that temperature in the cells can reach 34 degrees.

After a number of men attempted to escape this heat in the cells and tore a hole in the ceiling, the Northern Territory government did a comprehensive assessment to improve ventilation, with plans to put in more shading and evaporative cooling and airflow systems. But it does not plan to install air-conditioning.

Roebourne Regional Prison in Western Australia is commonly regarded as the hottest prison in the country. In July this year, following more than a decade of campaigning by advocates, the state government confirmed that all the cells at the prison now had air-conditioning.

The Tasmanian prison watchdog in 2018 raised serious concerns with extreme heat at the Launceston Reception Prison, saying that “female prisoners were seen coming out of cells gasping for air and dehydrated”.

“The female cells back onto a solid brick wall, which is a heat conductor, and there is no air ventilation,” the inspector said at the time.

The inspector found that concerned staff had recorded temperatures of up to 40 degrees at the prison over two nights in summer.

Following a recent inspection of the Bathurst Correctional Centre, the NSW prison inspector said that some areas of the prison were “dark, dilapidated, susceptible to extreme temperatures [and] lacking ventilation and natural light”.

It also said that the area set aside for people in prison to have video calls with their loved ones exposed them to extreme temperatures.

The inspector also said that heat at the Broken Hill Correctional Centre was “stifling”, with little relief available to those incarcerated there.

“The men had no capacity to cool down other than by using the water tap on top of the toilet cistern,” the inspector said.

The infrastructure at these prisons is from the 1800s, with windows that are always open, with temperatures at the prison ranging from -2.9 to 46.3 degrees, the watchdog found.

A spokesperson for NSW Corrections said that a Heat Event Response Plan is implemented during extreme heat, with enhanced ventilation, adjustments to daily routines during peak heat periods, additional hydration points and increased medical monitoring.

“To help manage heat inside accommodation areas, centres use a range of measures such as insulation, building design, air-conditioning where installed, and natural ventilation systems,” the spokesperson said.

“These approaches typically keep internal temperatures about eight to 12 degrees cooler than outside conditions.”

In Queensland prisons, air flow and temperature levels are monitored regularly, and there is a specialised unit within Queensland Corrective Services which “closely monitors and provides advice about how to manage high-risk weather, including heatwaves”.

Under a “safer cell design” program, more than 90 percent of prison cells in Queensland now have air-conditioning by default.

In Victoria, air-conditioning is only available in some accommodation units for “more vulnerable people”, a spokesperson said, including pregnant women, those with babies and the elderly.

In the ACT’s Alexander Manonochie Centre, the only cells with air-conditioning are in the Crisis Support Unit, with no plans to install cooling more widely.

The cells at the prison are designed “using passive solar principles, incorporating features such as strategic window placement, wall orientation, insulation and flooring materials to reduce heat during warmer months”.

There are no nation-wide policies or guidelines for managing extreme heat in Australian prisons, or for the regular measurement of temperatures within prison buildings and cells.

The “Guiding principles for corrections in Australia” from 2018 does not mention heat or temperature guidelines.

Should going to prison mean never being allowed to hug your partner or child? Is denying physical contact a just punishment, or does it harm families and human dignity? And what do human rights have to say about it?

While for the most part calls to mobiles are becoming cheaper, we clearly still have a long way to go.

Including seven children escaping youth detention in Tasmania, two men being charged over prison murder in Queensland, a coroner pushing for bans on spit hoods in prison in the Northern Territory and more.

A number of Victorian prisons may have to be renovated or rebuilt after the Supreme Court found that no “open air” was being provided to inmates in multiple units.

Help keep the momentum going. All donations will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. If you would like to pay directly into our bank account to avoid the processing fee, please contact donate@abouttime.org.au. ABN 67 667 331 106.

Help us get About Time off the ground. All donations are tax deductible and will be vital in providing an essential resource for people in prison and their loved ones.

Your browser window currently does not have enough height, or is zoomed in too far to view our website content correctly. Once the window reaches the minimum required height or zoom percentage, the content will display automatically.

Alternatively, you can learn more via the links below.

Leave a Comment

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere. uis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.